Casamance conflict

| Casamance conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

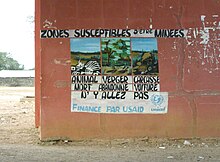

Painting in Oussouye warning of land mines in the area. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

300–600 (1989)[8] 2,000–4,000 (2004)[9] 180 (2006) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,000 killed in total since 1982[10] 60,000 internally displaced[11] | |||||||

The Casamance conflict is an ongoing low-level conflict that has been waged between the Government of Senegal and the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) since 1982. On May 1, 2014, the leader of the MFDC sued for peace and declared a unilateral ceasefire.

The MFDC has called for the independence of the Casamance region, whose population is religiously and ethnically distinct from the rest of Senegal.[12] The bloodiest years of the conflict were during the 1992–2001 period and resulted in over a thousand battle related deaths.[12]

On December 30, 2004, an agreement was reached between the MFDC and the government which promised to provide the voluntary integration of MFDC fighters into the country's paramilitary forces, economic recovery programmes for Casamance, de-mining and aid to returning refugees.[12] Nevertheless, some hard-line factions of the MFDC soon defected from elements of the MFDC who had signed the agreement and no negotiations took place following the breakdown of talks in Foundiougne on 2 February 2005.[12]

Fighting again emerged in 2010 and 2011 but waned following the April 2012 election of Macky Sall. Peace negotiations under the auspices of Saint Egidio community took place in Rome and on 14 December 2012, President Sall announced that Casamance would be a test-case for advanced decentralization policy.[12]

Background

[edit]

The distinct regional identity of the Casamance region has contributed to separatist arguments that distinguish the region and its people from the North.[13]

Geography

[edit]The Casamance region is the southern region of Senegal which, although connected in the East, is separated from the rest of Senegal. The Gambia divides Senegal along nearly 300 kilometers by a width of 50 kilometers.[14] Casamance contains two administrative regions named for their capitals: Ziguinchor to the west and Kolda to the east.[15] The Ziguinchor region has been the most affected by the conflict, where it was initially confined.[13][15] Beginning in 1995, the conflict spread into the Kolda region, largely affecting the department of Sédhiou.[15]

The region's terrain differs from that of the northern Sahel landscape. Casamance terrain is filled with rivers, forests, and mangrove swamps.[16]

Demographic and cultural differences

[edit]The principal inhabitants of the region are members of the Jola (Djiola, Diola) ethnic group,[12] although they are overall a minority if all other ethnic groups of Casamance are combined. Besides Jola, the area also harbors Mandinka, Mankanya, Pulaar (a Fula group), Manjak, Balanta, Papel, Bainuk, and a small minority of Wolof.[3] By contrast, the Wolof are the overall largest ethnic group in Senegal, dominating the north.[16] The sentiment has existed amongst Jola that they do not benefit sufficiently from the region's richness and that Dakar, the capital, reaps most of the profit from the region's products.[12] This feeling of unequal treatment is widespread in Casamance, even among those who do not support separatism.[3] Many people within Casamance are Christians or animists, unlike the majority of Senegalese who are Muslims.[12] However, relations between Senegal's Muslim and Christian populations have historically been mutually respectful.[17][3] Religion has played no important part in the Casamance conflict.[9]

Colonial rule

[edit]Though Senegal was colonized by France in the nineteenth century, Portugal was the first European country to make contact with the country.[17] Portuguese administration was established in Ziguinchor in 1645 and remained until 1888.[14] In the period which followed, French, Portuguese, and British powers competed for influence in the area.[18] After French colonial rule was established, French Catholic missionaries concentrated their efforts among Jola in lower Casamance, along with the Serer ethnic group.[17] The first proposal for the autonomy of Casamance emerged under French rule.[3]

Timeline

[edit]1970s

[edit]In the late 1970s, a separatist movement first developed in Casamance. Political frustrations mounted from the lack of economic growth for Casamançais people. One of the recurring themes was that Northerners dominated the economy of the region.[19] The administration in Ziguinchor was dominated by Northerners, predominantly of the Wolof ethnic group.[20][14] Zinginchor and coastal areas underwent developmental expropriations, and many local officials from the northern regions gave relatives and clients access to land. This resulted in protests in Ziguinchor and Cap Skirring.[21]

1980s

[edit]In the 1980s, resentment about the marginalization and exploitation of Casamance by the Senegalese central government gave rise to an independence movement in form of the MFDC, which was officially founded in 1982. This initial movement managed to unite Jola and other ethnic groups in the region, such as Fulani, Mandinka and Bainuk, and led to rising popular resistance against the government and northerners.[22]

On December 26, 1982, several hundred protesters gathered in Ziguinchor despite the arrest of most of the demonstration's leaders.[21] This peaceful demonstration was attended by men and women of all classes as well as of Jola and other ethnic groups in the region. During the event, the protestors marched to the regional governor's office and replaced the Senegalese flag with a white flag. In response, the Senegalese government targeted Jola people.[20]

The MFDC began to organise demonstrations, and tensions eventually escalated in massive riots in December 1983. On December 6, three gendarmes were killed while intervening at a MFDC meeting near Ziguinchor.[21] On December 18, 1983, militants with weapons marched in Ziguinchor. This demonstration turned violent, with many casualties.[21] Following this attack, the Senegalese government drove the MFDC underground into the forests. This caused the MDFC to form a more radicalized, armed wing that engaged in guerrilla combat against the Senegalese army and symbols of statehood[20] in 1985. The armed wing was known as Attika ("warrior" in Diola).[9] The Senegalese government answered by dividing the Casamance province into two smaller regions, probably in order to split and weaken the independence movement. This only heightened tensions, and the government began to jail MFDC leaders such as Augustin Diamacoune Senghor.[22]

Another factor in the growing independence movement was the failure of the Senegambia Confederation in 1989, which had economically benefited Casamance and whose end only worsened the situation of Casamance's population.[22] By the end of the 1980s, the military wing of the MDFC had an estimate of 300-600 trained fighters.[8]

1990s

[edit]

The discovery of oil in the region emboldened the MFDC to organise mass demonstrations for immediate independence in 1990, which were brutally suppressed by the Senegalese military. This pushed the MFDC into a full armed rebellion. The following fighting was vicious, and 30,000 civilians were displaced by 1994. Several ceasefires were agreed during the 1990s, but none lasted, often also due to splits within the MFDC along ethnic lines and between those ready negotiate and those who refused to lay down their weapons. In 1992 the MFDC divided into two main groups, Front Sud and Front Nord. Whereas Front Sud was dominated by Jola and called for full independence, Front Nord included both Jola as well as non-Jola tribesmen and was ready to work with the government based on a failed agreement of 1991.[24] Another ceasefire in 1993 led to the break-off of hardline rebel groups from the MFDC. These continued to attack the military.[6] In 1994, Yahya Jammeh took power in the Gambia through a coup d'état. Jammeh would start to provide the MFDC with substantial support,[3] and was even known to recruit MFDC fighters into the Gambian military, reportedly since they were more inclined to be loyal to Jammeh's regime than the people of the Gambia.[25]

The Senegalese military relocated thousands of soldiers from the northern provinces to Casamance in 1995 in an attempt to finally crush the uprising. The northern soldiers often mistreated the local population and did not differentiate between those who supported the rebels and government loyalists. By this time, the rebels had established bases in Guinea-Bissau, reportedly being supplied with arms by Bissau-Guinean military commander Ansumane Mané. Mané's alleged support for the separatists was one factor which led to the Guinea-Bissau Civil War that erupted in 1998. When Senegal decided to send its military into Guinea-Bissau to fight for the local government against Mané's forces, the latter and the MFDC formed a full alliance. The two rebel movements started to fight side by side in both Senegal as well as Guinea-Bissau.[6] Although the Senegal-supported government of Guinea-Bissau collapsed, the following MFDC-sympathetic regime was also overthrown in May 1999.[5] Meanwhile, tensions within the MFDC resulted in rebel leader Salif Sadio killing 30 of his rivals; however, one of his main opponents among the insurgents, Caesar Badiatte, survived an assassination attempt.[3]

In a renewed offensive against the separatists between April and June 1999, the Senegalese military shelled Casamance's de facto capital Ziguinchor for the first time, causing numerous civilian casualties and the displacement of 20,000 people along the Senegal–Guinea-Bissau border. From then on, fighting mostly took place in the eastern Kolda Region. Another attempt at peace talks started in December 1999, with Senegalese and MFDC representatives meeting in Banjul. Both sides agreed to a ceasefire.[26] By the end of the 1990s, the MFDC had made little progress in both its diplomatic as well as militant attempts at furthering its cause. In addition, the party's reputation as a genuine separatist forces started to suffer, as it became evident that many MFDC commanders were less motivated by politics and more by money in their insurgency. Several would accept ceasefires with the Senegalese government as long as they received rewards by the authorities.[9]

2000s

[edit]

Peace talks resumed in January 2000, with both sides attempting to end the military conflict and aiming at restoring political and economic normality to Casamance. Discussions were held about the MFDC transforming into a political party, but the talks were hindered by the MFDC's factionalism, and the refusal of the Senegalese government to even consider Casamance's independence. As result, the peace talks collapsed in November 2000, with MFDC leader Augustin Diamacoune Senghor declaring that his group would continue to fight until achieving independence. A new ceasefire was agreed to in March 2001, but failed to stop the conflict. Meanwhile, internal divisions deepened among the MFDC about the movement's aims and Senghor's leadership.[26]

On 30 December 2004, the two sides of the conflict signed a truce, which lasted until August 2006.

Since the split, low-level fighting has continued in the region. Another round of negotiations took place in 2005.[27] Its results proved partial, and armed clashes between the MFDC and the army continued in 2006, prompting thousands of civilians to flee across the border to the Gambia.[28] At the same time, the MFDC factions of Sadio and Badiatte also fought each other.[3]

On 13 January 2007, Senghor died in Paris. His death hastened the split of the MDFC, which divided into three major armed factions, led by Salif Sadio, Caesar Badiatte, and Mamadou Niantang Diatta respectively.[4] In addition, several smaller groups also emerged later on. Sadio claimed overall leadership of the MFDC's armed wing.[3]

On 9 June 2009, radical MDFC militants killed a former MFDC member, who at the time was serving as a peace process mediator.[citation needed]

2010s

[edit]

In October 2010, an illegal shipment of arms from Iran was seized in Lagos, Nigeria. The Senegalese government suspected that the arms were destined for the Casamance, and recalled its ambassador to Tehran over the matter.[30] Heavy fighting occurred in December 2010 when about 100 MDFC fighters attempted to take Bignona south of the Gambian border supported by heavy weapons, such as mortars and machine guns. They were repulsed with several casualties by Senegalese soldiers who suffered seven dead in the engagement.[31]

On 21 December 2011, Senegal media reported that 12 soldiers were killed in Senegal's Casamance region following a separatist rebel attack on an army base near the town of Bignona.[32]

Three soldiers were killed during a clash 50 kilometers (31 mi) north of Ziguinchor. The Senegalese government blamed the conflict on separatists in the region on February 14, 2012.[33]

Two attacks occurred on 11 and 23 March 2012, leaving 4 soldiers killed and 8 injured.[34]

Since April 2012, peace in the Casamance has been a top priority for the administration of Senegalese President Macky Sall.[35]

On 3 February 2013, four people were killed during a bank robbery perpetrated by the MFDC in the town of Kafoutine; the rebels stole a total of $8,400.[36]

On 1 May 2014, one of the leaders of the MFDC, Salif Sadio, sued for peace and declared a unilateral ceasefire after secret talks held at the Vatican between his forces and the Government of Senegal led by Macky Sall.[7] Sadio consequently lost much power among MFDC, with much of the movement no longer regarding him as leader.[3]

In 2016, a presidential election resulted in the surprise defeat of Yahya Jammeh who had ruled the Gambia autocratically since 1994. He refused to accept his defeat, leading to a constitutional crisis.[3] The Economic Community of West African States responded with a military intervention in 2017 during which MFDC rebels supported pro-Jammeh forces.[37] Jammeh ultimately fled, resulting in Adama Barrow becoming the Gambia's president; he was known as being close to Macky Sall, meaning that the MFDC lost an important foreign ally.[3]

Members of the group were suspected of being behind an ambush that left 13 people dead near the town of Ziguinchor on 6 January 2018.[38] Leaders of the MFDC, however, have denied responsibility for the execution-style killing, which they say was connected with the illegal harvesting of teak wood and rosewood from the forested region, not the gathering of firewood.[39]

2020s

[edit]By 2020, most MFDC factions, including those of Badiate and Sadio, were still upholding ceasefires. In April of that year, tensions in the MFDC's Sikoun faction operating in the Goudomp Department resulted in a split. Diatta, until then leader of the faction, fell under suspicions of being in contact with the government. Adama Sané consequently assumed command of the Sikoun faction, even though Diatta maintained his own following.[3] There was a general lull in fighting during 2020. However, an ally of Senegalese President Macky Sall, Umaro Sissoco Embaló, became President of Guinea-Bissau in that year, resulting in an increased cooperation of the countries.[3][2]

On 26 January 2021, the Armed Forces of Senegal began an offensive against the MFDC factions of Sané and Diatta.[3] The operation included 2,600 infantry, 11 Panhard AMLs, as well as artillery, and was supported by the Senegalese Air Force. The Senegalese forces were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Mathieu Diogoye Sène and Lieutenant Colonel Clément Hubert Boucaly.[3] With aid by the military of Guinea-Bissau, Senegalese troops overran four MFDC bases in Blaze forest during February, namely those at Bouman, Boussouloum, Badiong, Sikoun.[2][3] The MFDC also alleged the involvement of the Turkish Armed Forces on the side of Senegal.[3] At Badjom, the government forces seized a significant amount of rebel weaponry including mortars.[2] The Senegalese troops also seized several hectares of marijuana cultivation.[40] Both the military as well as the rebels claimed to have inflicted casualties on each other.[3] Despite the offensive's success, the Senegalese military admitted that several rebel bases remained active,[2] as neither the hardline Diakaye faction of Fatoma Coly (which supports Sané and Diatta) nor the groups of Sadio and Badiatte had been targeted.[3] However, security analyst Andrew McGregor argued that the ease with which the Senegalese military had overrun the MFDC bases during the offensive pointed at the separatists having become extremely weak. He concluded that "the movement has clearly lost any broad support it might have once enjoyed".[3]

From May to June 2021, the Senegalese military launched another counter-insurgency operation, this time in the area around Badème. Its aim was to close the border to Guinea-Bissau for the rebels and reduce wood as well as drug smuggling, and the army claimed to have captured several MFDC posts and bases.[41] In January 2022, MFDC rebels attacked Senegalese soldiers operating as part of the ECOWAS mission in the Gambia, killing four and capturing seven. Though the prisoners were later released, the Senegalese military took this incident as reason for launching an operation against the Sadio faction which operated at the Senegalese-Gambian border. The offensive started on 13 March 2022,[42] and caused 6,000 civilians to flee across the border into the Gambia.[43]

In early August 2022, Caesar Badiatte signed a peace deal with the Senegalese government following mediation by Guinea-Bissau's President Umaro Sissoco Embaló. Though Badiatte only agreed on behalf of his faction, the government expressed hope that other MFDC groups would join the agreement.[44]

References

[edit]- ^ Minahan 2002, pp. 400–401.

- ^ a b c d e f "Senegal says troops overrun rebel camps in Casamance region". Africa News. AFP. 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Andrew McGregor (21 February 2021). "Is the Curtain Dropping on Africa's Oldest Conflict? Senegal's Offensive in the Casamance". Aberfoyle International Security. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Christophe Châtelot (19 June 2012). "Boundaries of Casamance remain blurred after 30 years of conflict". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b Minahan 2002, pp. 400, 401.

- ^ a b c d Minahan 2002, p. 400.

- ^ a b "Senegal: Movement for the Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) rebels declare unilateral truce » Wars in the World". Warsintheworld.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ a b Lambert, Michael C. (1998). "Violence and the war of words: ethnicityv.nationalism in the Casamance". Africa. 68 (4): 585–602. doi:10.2307/1161167. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1161167. S2CID 145231552.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2016, Casamance.

- ^ "Casamance: no peace after thirty years of war". Guinguinbali.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013.

- ^ Harsch, Ernest (April 2005). "Peace pact raises hope in Senegal". Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Database – Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)". Ucdp.uu.se. Archived from the original on 2017-10-01. Retrieved 2016-11-02.[verification needed]

- ^ a b Gehrold, Stefan; Neu, Inga (2010). "Caught Between Two Fronts – In Search of Lasting Peace in the Casamance Region: An Analysis of the Causes, Players and Consequences". Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Bruce Berman; Dickson Eyoh; Will Kymlicka (2004). Ethnicity & democracy in Africa. Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-4267-8. OCLC 1162026740. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Evans, Martin (2007-03-01). "'The Suffering is Too Great': Urban Internally Displaced Persons in the Casamance Conflict, Senegal". Journal of Refugee Studies. 20 (1): 60–85. doi:10.1093/jrs/fel026. ISSN 0951-6328. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2021-04-22.

- ^ a b Clark, Kim Mahling (2009). "Ripe or Rotting: Civil Society in the Casamance Conflict". African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review. 1 (2): 153–172. doi:10.2979/africonfpeacrevi.1.2.153. JSTOR 10.2979/africonfpeacrevi.1.2.153. S2CID 144513363. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2021-04-22 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Ross, Eric (2008). Culture and customs of Senegal. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-34036-9. OCLC 191023999. Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Faye, Ousseynou (1994). "L'instrumentalisation de l'histoire et de l'ethnicité dans le discours séparatiste en Basse Casamance (Sénégal)". Africa Spectrum. 29 (1): 65–77. ISSN 0002-0397. JSTOR 40174512. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Foucher, Vincent (2019). "The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal?". In Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus (eds.). Secessionism in African politics aspiration, grievance, performance, disenchantment. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 265–292. ISBN 978-3-319-90205-0.

- ^ a b c Theobald, Anne (2015-04-03). "Successful or Failed Rebellion? The Casamance Conflict from a Framing Perspective". Civil Wars. 17 (2): 181–200. doi:10.1080/13698249.2015.1070452. ISSN 1369-8249. S2CID 146234666. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ a b c d Foucher, Vincent (2019). "The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal?". In Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus (eds.). Secessionism in African politics aspiration, grievance, performance, disenchantment. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 265–292. ISBN 978-3-319-90205-0.

- ^ a b c Minahan 2002, p. 399.

- ^ Minahan 2002, p. 396.

- ^ Minahan 2002, pp. 399, 400.

- ^ "Gambia: Why the army may be the key to getting Jammeh to step down". African Arguments. 2016-12-16. Archived from the original on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- ^ a b Minahan 2002, p. 401.

- ^ "Senegal to sign Casamance accord". BBC. 30 December 2004. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ "Attacks in Casamance despite peace move". Irin News. 5 December 2006. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "Gunmen kill 13 in Senegal's Casamance region - army". Reuters. 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Senegal recalls Tehran ambassador over arms shipment". BBC News. 15 December 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Senegalese army sweeps Casamance after fight with separatists". RFI. 28 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "12 Soldiers killed as violence in Senegal continues". Sabc.co.za. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Senegalese troops 'killed in attack'". Al Jazeera. 14 February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Soldier Killed, Four Wounded In Senegal Rebel Attack". Modern Ghana. 23 March 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "Activities – Senegal". Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ^ "Casamance separatist insurgency kills four". Reuters. 3 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Kwanue, C. Y. (18 January 2017). "Gambia: Jammeh 'Imports Rebels'". allAfrica. Archived from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Gunmen killed at least 13 people Saturday in Senegal who were gathering firewood in the forest, the military said". France24. 6 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ "Rebels blame Casamance massacre on logging feud". Pulse News Agency International by AFP. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Senegalese army seizes cannabis fields and rebel forest bases". news.yahoo.com. AFP. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "MDFC rebel base captured in Casamance by Senegalese military operation". Africa News. AFP. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Senegal launches operation against rebels in Casamance". Africa News. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Operation Casamance: At least 6,000 people flee to the Gambia". Africa News. 20 March 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Senegal Peace Deal 'Important Step' – Mediator". VOA. 5 August 2022. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

Works cited

[edit]- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World: A-C. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32109-4.

- Williams, Paul D. (2016). War and Conflict in Africa. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1509509058.

Further reading

[edit]- Fall, Aïssatou (2011). "Understanding The Casamance Conflict: A Background". KAIPTC Monograph No. 7. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- Eric Morier-Genoud, "Sant’ Egidio et la paix. Interviews de Don Matteo Zuppi & Ricardo Cannelli", _ LFM. Sciences sociales et missions _, Oct 2003, pp. 119–145

- Foucher, Vincent, ‘The Mouvement Des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal?’, in Secessionism in African Politics Aspiration, Grievance, Performance, Disenchantment, ed. by Lotje de Vries, Pierre Englebert, and Mareike Schomerus (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 265–292

- Casamance

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Civil wars of the 20th century

- Civil wars of the 21st century

- 1980s conflicts

- 1990s conflicts

- 2000s conflicts

- Conflicts in 2010

- Conflicts in 2011

- Conflicts in 2012

- Conflicts in 2013

- Conflicts in 2014

- Conflicts in 2015

- Conflicts in 2016

- Conflicts in 2017

- Conflicts in 2018

- Conflicts in 2019

- Conflicts in 2020

- Conflicts in 2021

- Conflicts in 2022

- Conflicts in 2023

- Conflicts in 2024

- 1980s in Senegal

- 1990s in Senegal

- 2000s in Senegal

- 2010 in Senegal

- 2011 in Senegal

- 2012 in Senegal

- 2013 in Senegal

- 2014 in Senegal

- 2015 in Senegal

- 2016 in Senegal

- 2017 in Senegal

- 2018 in Senegal

- 2019 in Senegal

- 2020 in Senegal

- 2021 in Senegal

- 2022 in Senegal

- 2023 in Senegal

- 2024 in Senegal

- Separatism in Senegal

- Separatist rebellion-based civil wars

- Wars involving Senegal

- Military of Senegal

- Politics of Senegal

- Political violence in Senegal

- Wars involving Guinea-Bissau

- The Gambia–Senegal relations

- Wars involving the Gambia

- Guinea-Bissau–Senegal relations